How to Watch Drive as a Crime Fiction Writer

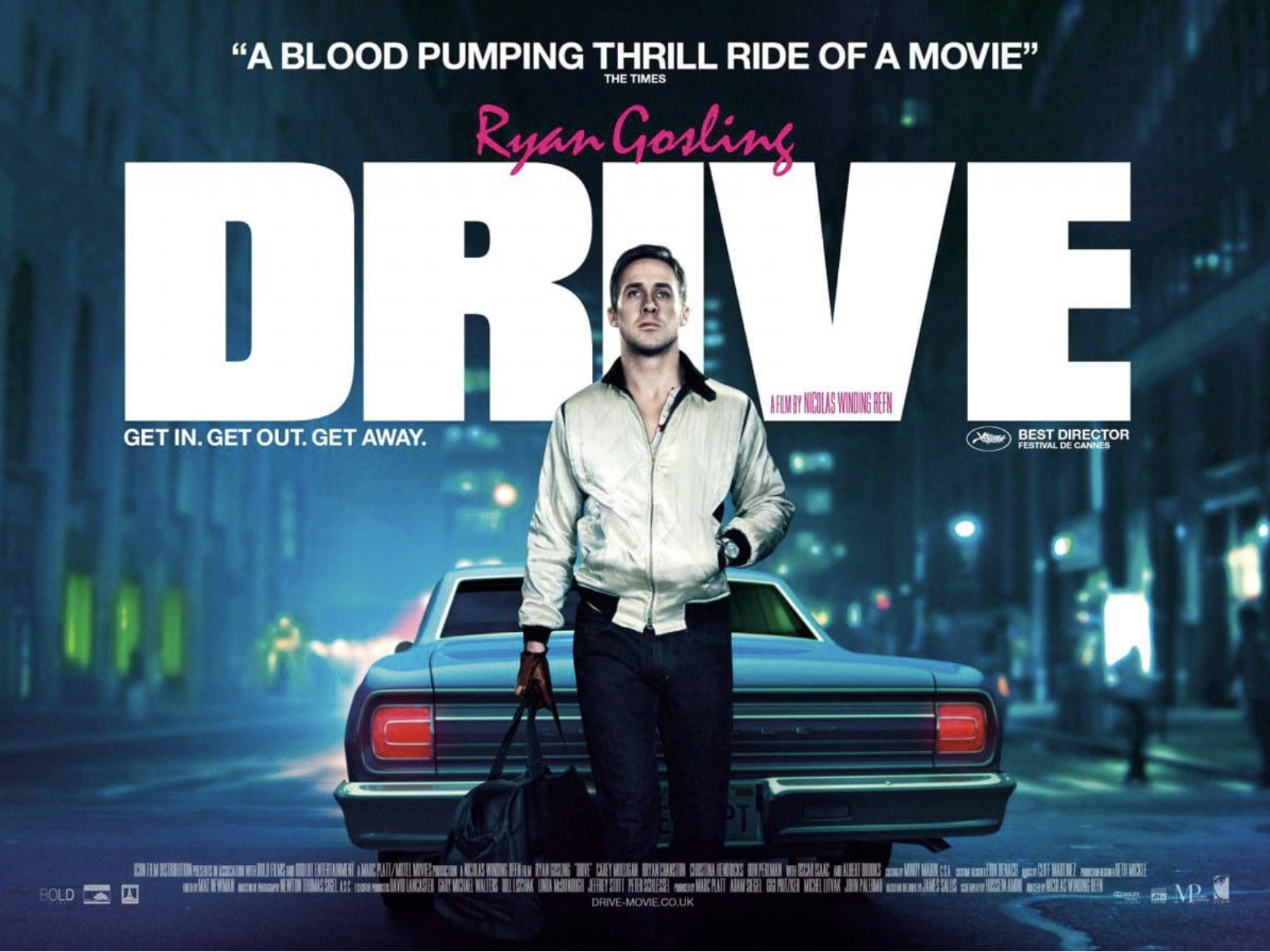

Ryan Gosling in Drive

When James Sallis died, I found myself returning to Drive, the novel that inspired Nicolas Winding Refn’s film. Sallis—contemporary of Elmore Leonard and James Ellroy—was always something rarer: literary, elliptical, resistant to formula. He didn’t comfort crime readers with familiar scaffolding. He pushed at the genre’s boundaries.

And in Drive, he may have helped redefine it.

The film adaptation became sleek, violent, and iconic. But beneath the neon and 80’s synth score is something more enduring for crime writers: a meditation on individualism, personal code, and the lone protagonist navigating a hostile world.

James Sallis: When the Writing Is the Story

Few readers come to Sallis for pure narrative propulsion. Even in Drive, plot is secondary to language and interiority. His protagonist—known only as Driver—is a skilled wheelman and capable of brutal violence. But those are surface traits. Sallis is as invested in a perfectly turned simile as he is in a shootout.

Elmore Leonard famously said, “If it looks like writing, I take it out.”

If you removed what “looks like writing” in Sallis, the novel would collapse into an inky puddle of pulp residue. The prose is the glue. The artistry is the point.

That commitment to language is precisely why Sallis is admired by writers and less widely consumed by mass audiences. He privileges atmosphere and interior life over structural neatness.

From Literary Noir to Neon Myth

There’s a reason Drive attracted major talent and a high-budget adaptation. At its core is a volatile character dropped into a high-stakes scenario, with potential for the kind of high-octane car chase scenes that made the Fast and Furious franchise so immense.

The film (in Hossein Amini’s deft adaptation) reshapes Sallis’s loose, time-jumping structure into something more emotionally direct. The romantic thread—muted and fragmented in the novel—becomes the film’s narrative spine. The adaptation trades literary abstraction for cinematic experience.

Where the novel ends in bleak catharsis, the film offers something closer to mythic redemption.

That shift matters.

Because what the film ultimately foregrounds is not plot—but ethos.

Driver about the rain hell on the threat

Rugged Individualism and the American Crime Hero

“He existed a step or two to one side of the common world, largely out of sight, a shadow, all but invisible. Whatever he owned, either he could hoist it on his back and lug it along or he could walk away from it. Anonymity was the thing he loved most about the city, being a part of it and apart from it at the same time.” ― James Sallis, Drive

Drive is a study in American rugged individualism.

The term is often admired in art more than practiced in life. Strip it down, give it a getaway car and a license to kill, and you have Driver: a lone man governed by an internal code, navigating a corrupt social order.

Like classic hardboiled fiction and film noir, Drive centers on the solitary protagonist facing layered antagonistic forces. In that sense, Driver is less a modern criminal than a modern cowboy. His car is his horse, and the bleak Los Angeles cityscape is his frontier.

The crime and western genres have long inverted traditional morality. The heroes are rarely sheriffs or police; they’re outlaws with codes. Driver, introduced as a getaway driver—basically an Uber driver for the underworld—is morally compromised from the outset. Yet his adherence to a personal code elevates him.

Ryan Gosling’s performance deepens this. He imbues Driver with warmth and restraint, transforming what could have been a nihilistic antihero into something approaching nobility.

The Personal Code as Narrative Engine

Look at Clint Eastwood’s westerns—Pale Rider, High Plains Drifter. The lone man survives not by adapting to a corruptible society, but by refusing to compromise.

That refusal creates conflict.

Without the code, there is no story.

Driver’s code compels him to intervene when his neighbor and love interest, Irene, and her young son are threatened. His attachments to this small family he swore to protect reorganize, or galvanize, his moral universe. Unlike the novel’s more nihilistic Driver, the film’s version is capable of loyalty and sacrifice.

This is a crucial adaptation shift: the film gives him something to lose. And because he has something to lose, he has something to defend.

Lineage: From Thief to Drive

If Drive shares a cinematic ancestor, it is Michael Mann’s Thief.

James Caan’s Frank is another professional criminal bound by discipline and a personal code. Like Driver, Frank must ultimately burn down his attachments to survive. The system will exploit and leverage whatever he loves against him.

The difference is emotional texture. Frank is Zen-like in his detachment. Driver is not. His vulnerability—his connection to Irene—complicates his stoicism.

The novel denies redemption. The film cannot.

The ending—Driver wounded but alive, driving into the Los Angeles night—offers not triumph, but continuity. He survives. The code survives, and that is enough.

The Disappearing Lone Male

In more recent crime films, this archetype has softened. The hyper-competent, morally coded lone man has increasingly given way to ironic, bumbling, or self-conscious protagonists.

One could argue that contemporary culture is uneasy with this figure. The American male antihero is being detoxified.

Gosling, in roles like Driver and Luke in The Place Beyond the Pines, stands in lineage with Paul Newman, Steve McQueen, and James Caan—actors who embodied danger without apology.

In Drive, violence is not explained away by trauma. It simply is. The film trusts the audience to sit with that.

That trust is increasingly rare.

Ride shares for the underworld

What Crime Writers Can Learn from Drive

1. Individualism creates conflict.

When a protagonist adheres to a private code in a compromised society, friction is inevitable.

2. A personal code is more powerful than shared morality.

It’s less didactic and more dramatically expressive.

3. Lone protagonists allow projection.

Readers can both inhabit and judge them.

In many manuscripts I edit, writers try to integrate their protagonists into society—to soften them, to justify them. But estrangement is often the narrative engine. The outsider status is not a flaw, but fuel for conflict.

Final Takeaway: Integrity Over Homogenization

Can characters like Driver survive in an increasingly antiseptic cultural landscape?

Only if writers are willing to risk writing them.

Sallis never wrote for comfort. He wrote for integrity. The genre was not something to conform to—it was something to shape.

Hardboiled noir was already cliché when Sallis entered it. He bent it toward poetry and myth. The film adaptation bent it toward iconography.

The lesson for crime writers is simple:

Create from your own code.

Let the character’s code collide with the world.

Don’t compromise either.

Matt Henderson Ellis is a writer and developmental editor.