How to Watch Devil in a Blue Dress as a Crime Fiction Writer

Denzel Washington as Easy Rawlins, with Jennifer Beals as Daphne Monet.

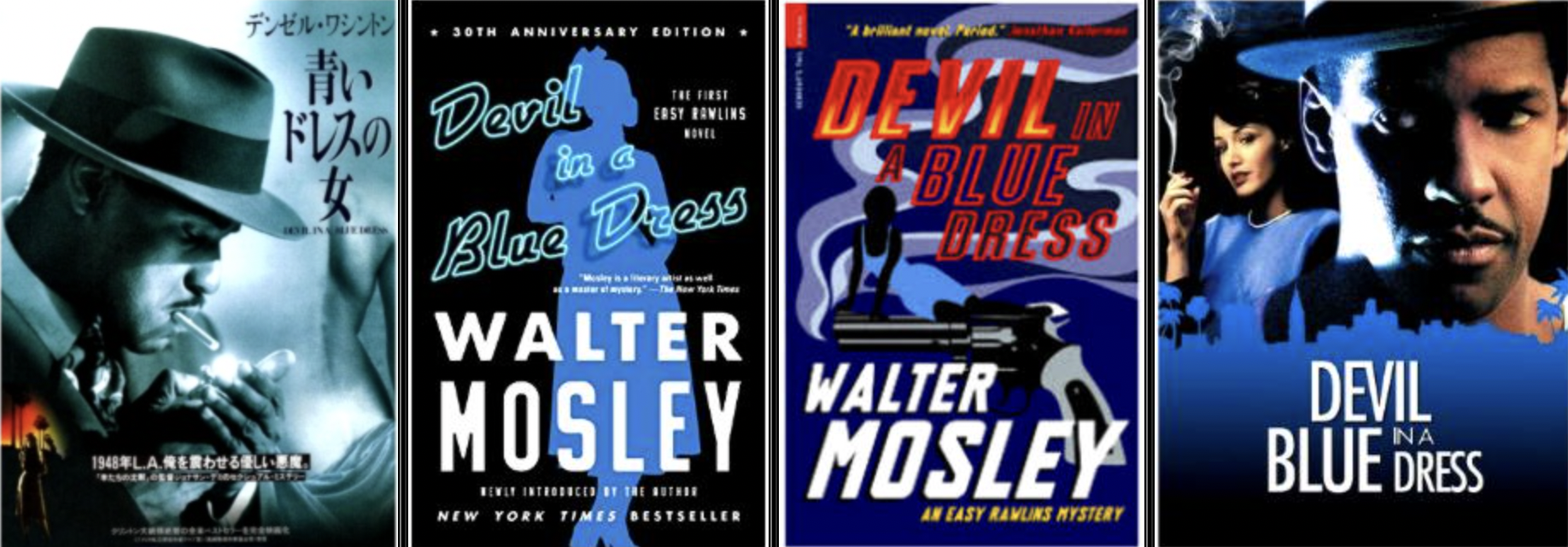

In Devil in a Blue Dress, Walter Mosley begins with a familiar noir proposition: an unemployed man, a desperate need for cash, and a job that looks easier than it is. What follows is not simply a mystery, but a study in how crime fiction elevates stakes by turning social systems into antagonists. Easy Rawlins’ investigation unfolds in 1950s Los Angeles, where every choice is shaped, and constrained, by race, power, and institutional violence.

In Devil in a Blue Dress, Easy, an unemployed machinist, makes a deal with the devil. Like most such bargains, it appears relatively innocent at first—an easy solution to mounting financial pressure. All Easy Rawlins has to do is find a woman. A white woman, in historically Black Watts, Los Angeles.

That task alone carries risk in 1950s Los Angeles. Once Easy accepts the money, however, the stakes escalate quickly. A series of misadventures place him at two murder scenes, and the simple job transforms into a fight for survival. Each a small decision comes with catastrophic consequences, set in motion by forces far larger than the protagonist himself.

This is the narrative engine of Walter Mosley’s first novel, capably, and largely faithfully, rendered on the big screen by director Carl Franklin.

Reinventing the Hardboiled Tradition

Mosley’s story is cut from the same cloth as Raymond Chandler and John D. MacDonald’s best work—hardboiled, morally ambiguous, unsentimental. But it is also armed with its own aesthetic and concerns.

Rather than merely inhabiting the genre, Mosley retools it. He mines the lived history of postwar Black America and turns traditional power structures on their head. Expectations of who the protagonist is allowed to be—what he can do, where he can go, how he is perceived—are rewritten, and in doing so, reinvented.

Race as a Force Multiplier in Crime Fiction

This post isn’t meant to confront race and racism head-on as abstract subjects, but to examine how they function narratively—specifically, how they elevate conflict.

In crime fiction, systems and institutions often act as force multipliers in conflict. Like Chinatown, Devil in a Blue Dress raises its stakes by pitting the protagonist not against a single antagonist, but against a network of political corruption.

What makes Devil in a Blue Dress distinct is the hidden antagonist beneath all others: racism.

Because Easy Rawlins is Black in 1950s Los Angeles, his experience as a de facto investigator is fundamentally different from the detectives we’re accustomed to seeing on screen or page. He cannot move freely. He cannot travel safely into white neighborhoods. He cannot be seen with white women. He is stripped of rights in the eyes of the police.

Race functions here as a narrative constraint, narrowing Easy’s choices and raising the cost of every decision he makes.

Don Cheadle as Mouse

When Identity Shapes Plot

Race in Devil in a Blue Dress is not merely an attribute of the protagonist—it shapes the plot itself.

The femme fatale’s mixed-race heritage, and her decision to hide it from her fiancé—a powerful political figure running for mayor—sets the entire story in motion and ultimately provides its resolution. Easy is hired precisely because of his race, because he can go where white men cannot.

Every confrontation with hostile detectives, every threat of false charges, every racially charged insult pushes Easy toward action or reaction that is both pragmatic and deeply personal. The investigation becomes inseparable from his identity.

Battling a System, Not a Villain

What truly activates Easy Rawlins as a protagonist is that he is not battling a person—he is battling a system.

This elevates the script beyond titillation or moral puzzle-solving. Racism in the film is multi-faced, pervasive, and seemingly unkillable—a gorgon rather than a monster. Easy is not meant to defeat it. At best, he cuts off a head long enough to catch his breath.

Survival, not victory, is the goal.

Under these conditions, a “win” is provisional: a less odious politician is elected, the woman is lost, and the system continues humming—kept at bay for now.

Crime Fiction and the Antagonism of Systems

From Chinatown to L.A. Confidential, some of the strongest crime narratives pit their protagonists against institutional forces rather than single villains. Easy Rawlins, Jake Gittes, and Ed Exley are all shaped—and scarred—by this kind of opposition.

For crime writers, the lesson is clear: the larger the antagonistic force, the more it draws out of the protagonist.

Easy is forged by this experience. When it ends, he has discovered a new self—and a path forward that did not exist before.

Lessons for Crime Writers

1. Systems create deeper stakes than individuals.

An antagonist can be defeated. A system can only be endured or navigated.

2. Historical context matters.

Easy’s choices are shaped by what he is permitted to do—and what he is forced to accept. Too many crime fiction manuscripts I edit rely on antagonists without examining the forces that shape, propel, and support them.

3. Character outweighs narrative momentum.

Mosley is willing to sacrifice propulsion for character depth, as he does in Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned. The result is moral complexity that lingers.

Final Takeaway

Perhaps the best advice to take from Devil in a Blue Dress is simply this: read Walter Mosley.

His plots are organic and meticulous. He understands morality and compromise. He inherited the noir tradition—and expanded it.

Hardboiled crime fiction was approaching cliché when Mosley arrived. He reinvented it for himself, and for the reader.

There is always room for a fresh take on an old genre—provided the writer understands exactly what the genre is made of.

Matt Henderson Ellis is a writer and crime fiction developmental editor.